By Tina Leto

The odds seem to be against uranium. Fukushima’s nuclear power plant is still disabled; the US Supreme Court seems to be leaning towards staying Virginia’s moratorium on uranium mining, and projects such as Berkeley Energía’s Salamanca mine in Spain are facing major opposition.

So, why mine uranium and why now?

The answer is quite simple, actually. There is increased demand, and, after a period of volatility, prices are going up.

A series of current events are increasing demand and pushing up the value of U308. Bank of America Merrill Lynch commodities team raised its uranium concentrate price estimates for 2018, 2019 and 2020 by 3%, 22% and 32%, respectively.

Cameco’s CEO Tom Gitzel has a bullish look on uranium but remarked prices still have a long way to go to create some sort of optimism in the market, things are moving forward, even if it is in a slow and steady pace. The current spot price is up 40% from last year and has reached its highest level in over two-and-a-half years at around $28.75/lbs.

So, what is happening?

First, we need to take into account that, nearly eight years after the Great East Japan Earthquake, the resource-poor country has already reactivated five nuclear plants and nine reactors and has approved a 20-year operations extension for the Tokai Daini reactor located some 115 kilometres northeast of central Tokyo.

Although it is unlikely that it achieves it by 2030 as promised by the government, the Land of the Rising Sun is working towards its goal of generating a fifth of its electricity from nuclear plants in the next decade. To achieve this, of course, they will need the raw material, uranium.

Then we have China, whose uranium demand is expected to grow to around 10,800 tonnes by 2020 and rise to between 16,300 tonnes and 18,500 tonnes by 2025. The Xi administration has said it will spend $2.4 trillion to expand its nuclear power generation by 6,600% and in the near term, it plans to connect five reactors to the electricity grid and start building six to eight additional units.

In Southeast Asia, India is carrying out an aggressive growth policy reliant on nuclear power that uses both local and imported uranium. At present, the subcontinent has 22 nuclear reactors, 14 of which use foreign inputs, and it is in the process of finishing up six new units. In the next few years, 19 reactors are expected to be built.

In the Middle East, Saudi Arabia commenced reactor procurement discussions with supplier countries, as it plans to build two large nuclear power reactors and projects 17 GWe of nuclear capacity by 2040 to provide 15% of the kingdom’s power.

Canada, on the other hand, just launched its Small Modular Reactor Roadmap to promote the construction of such infrastructures, which are capable of generating up to 300 MW for small and remote communities and mines that are not connected to the electric grid.

As all of this is happening, supply is starting to see cuts given the decision by Canada’s Cameco to suspend its McArthur River/Key Lake operations in Saskatchewan, the world’s largest uranium mine, and the resolution of Kazakhstan’s state-owned Kazatomprom to lower output by 20% over the next three years as well as perform another 6% production cut over previous expectations.

In addition to the reduced supply, Kazatomprom recently sold 8.1 million lbs of its annual production to Yellow Cake, a new uranium holding company that raised $200 million in a London-based IPO and whose management is buying and storing large amounts of the metal in anticipation of higher prices.

Back in March, the World Nuclear Association reported that there are 448 reactors operative and 57 new reactors under construction, 158 reactors planned or on order, and another 351 proposed. The need for uranium is there and it is not going anywhere. Financial advisors believe that global consumption will grow from about 172 million lbs in 2017 to some 190 million lbs in 2019 while a supply gap should be in place by 2022-2023.

The balance seems to be slowly shifting into a deficit for the first time in more than a decade and, on top of all the cuts previously mentioned, the decision of producers like Cameco to buy larger quantities of material from the spot market going forward to fulfill long-term sales contracts will add upward pressure to the prices.

A drill hole away from a game changer

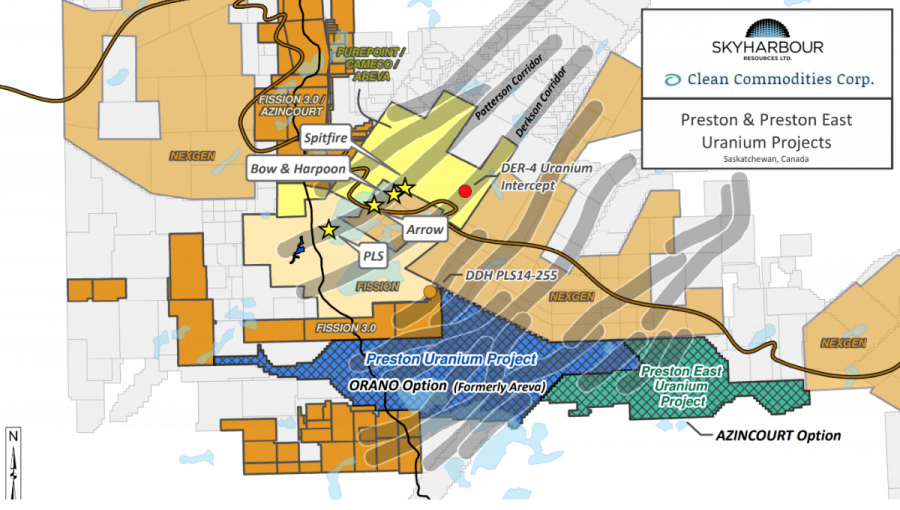

In other words, now is the time to invest in uranium stocks. With three projects underway, Azincourt Energy Corp (TSX.V: AAZ) is betting on a bright nuclear future. The primary focus of the Vancouver-based explorer and developer is its advanced exploration joint-venture with Skyharbour Resources, the 25,000+ ha East Preston Project, located in the Athabasca Basin, Saskatchewan where their team generated new drill targets to follow up after a successful geophysical exploration program.

Azincourt President and CEO Alex Klenman “These targets are similar to NexGen’s Arrow deposit and Cameco’s Eagle Point mine. East Preston is near the southern edge of the western Athabasca Basin, where targets are in a near surface environment without Athabasca sandstone cover.”

This region is gathering a lot of attention lately, especially after Skyharbour’s option partner Orano Canada (formerly Areva) announced last week that it plans to spend $2.22 million over the next year on exploration and drilling programs at the Preston project, which is right next door to the Azincourt/Skyharbour JV on East Preston.

In the next six years, big player Orano may end up investing about $6.04 million on exploration at Preston in exchange for up to 70% of the project. This is a hot zone of exploration with the Preston property and Azincourt/Skyharbour’s East Preston to be drilled at the same time. Who will make the first major discovery is anyone’s guess but, as always, it only takes one drill hole to transition from dwarf to giant.

And Azincourt seems to be betting at growing big time in the uranium space. Besides East Preston, the company led by Alex Klenman carries 10% of the Fission 3.0 Patterson Lake North project in Athabasca, and it recently acquired three highly prospective Peruvian-based properties known as the Escalera Group.

The South American project consists of three concessions occupying over 7,400 hectares on the Picotani Plateau, which have yielded historical samples of 6500 ppm uranium and recent samples of 3500 ppm uranium. Escalera is currently undergoing a mapping and sampling program.

According to Azincourt’s management, this latter grassroots play in an emerging uranium district combined the firm’s presence in the world-famous Athabasca basin are the well-founded pillars that boost its confidence in the silvery-white metal.

About the author: Tina Leto is a seasoned Canada-based writer focusing on the resource world.