By James Kwantes

Foreword: This tale grew from a chance nugget discovery along the shore of a humble Yukon creek carving through the remote Territory and became the great history of the Klondike Gold Rush. Join author James Kwantes as he touches down in the Yukon with 12 exciting stories and classic characters in this series that explores adventure, treasure and pain. Get your feet wet at Discovery Claim, Bonanza Creek. Catch the sparkle of Diamond-Tooth Gertie’s smile. And discover the Klondike connection to the Trump family fortune.

The Discovery

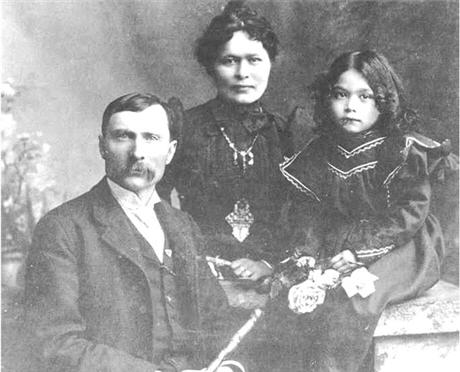

August 16, 1896: In a remote, cold and rather lawless corner of North America, an American prospector and three First Nations locals discover gold nuggets in a tributary of the Klondike River. The discoverers were George Carmack, his wife Kate Carmack (Shaaw Tlaa), her brother Skookum Jim and her nephew Dawson Charlie. The find secured their fortune, prompted a staking frenzy and landed the three men in the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame (1999). The gold rush they kicked off has produced 20 million ounces from Yukon gravels … and counting.

Methods used to mine the gold have shifted over the decades, from gold pans to mechanized dredges to modern mines. Historical oversights have been remedied, too. Earlier this year, Kate Carmack was inducted into the mining hall of fame, joining the other three discoverers and prospector Robert Henderson. George and Kate worked their claims at Rabbit Creek, renamed Bonanza Creek, for several years before moving to California, where George later abandoned her. The Yukon pioneer returned to the land where she found her fortune and died in 1920. Her legacy lives on. And so does the allure of gold, 123 years after the discovery …

The Gold Boats

August 16, 1896 marks the date gold was first discovered at Bonanza Creek. But the “gold rush” part actually took almost a year later to unfold. With no ships out of Yukon, the approaching deep freeze meant news of the strike did not travel too far, too quickly. But on July 15, 1897, the ship Excelsior sailed into San Francisco harbour, carrying Klondike prospectors and their tales of riches found. Two days later, the steamer Portland sailed into Seattle’s Elliott Bay carrying another 68 Klondike prospectors who had struck it rich. Both ships were laden with gold.

Like wildfire, news of the Klondike gold strike spread quickly. About 5,000 people — an estimated 10% of Seattle’s population — thronged to the docks as the Portland pulled in. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer chartered a tugboat to meet the boat; the newspaper’s headline screamed “Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold!” Seattle’s mayor, William Wood, quit and formed the Seattle and Yukon Trading Company, which chartered a steamship and charged $300 for passage north.

An estimated 70,000 people passed through Seattle en route to Dawson. The city’s population doubled between 1890 and 1900 and its economy boomed, laying the foundations for the modern Seattle. Some businesses established there during the flourishing gold rush have survived to this day, including Nordstrom, which opened in 1901 as a shoe store.

THE HARSH REALITY

After the Bonanza Creek strike, prospectors already in Yukon and Alaska moved quickly to stake the most promising claims. At the time, there were already an estimated 1,600 prospectors in the area, thanks to earlier gold finds. Some migrated from Alaska; others came from tributaries of the Yukon River where gold had been discovered earlier, such as the Fortymile River and Sixtymile.

These were by and large men forged by harsh winter conditions. The same can’t be said for many who flocked north in the summer of 1897. As author Pierre Berton put it, the Klondike “was just far enough away to be romantic and just close enough to be accessible.” In the years following the discovery, an estimated 100,000 adventurers surged north, by sea and land, to seek their fortunes. Many were ill-equipped, some by unscrupulous outfitters in Seattle and San Francisco.

The arduous journey up the Pacific coast, often on overcrowded and unsafe vessels, was just the start. After they arrived in Alaskan port cities, there was the mountainous trek inland to the headwaters of the Yukon River. The North West Mounted Police required that Klondike-bound stampeders carry at least a year’s worth of supplies. That meant multiple round trips up treacherous mountain passes such as the Chilkoot Pass. Then another 800-kilometre voyage down rapids and through canyons to Dawson City.

Only an estimated 30,000 stampeders made it that far. The ones who did endured dark, bitterly cold winters and fought disease and malnutrition along with the elements. Few struck it rich. But some struck it very rich ….

The Klondike Kings: Anton Stander

Prospectors who staked early claims along the most productive gold-bearing creeks, such as Bonanza and Eldorado, became fabulously wealthy. They were known as the “Klondike Kings”, and most of them epitomized the rags-to-riches aspirations of stampeders. Many of them, including Anton Stander, also made the return trip to rags. Stander immigrated to New York in 1887 with just a dollar and seventy-five cents to his name. He left Yukon (along with his favourite dancing girl) as the Klondike’s fourth richest man.

Stander was born in modern-day Austria in 1867 and worked in America as a cowboy, coal miner, sheep-herder and waiter. In the spring of 1896, he sold everything and journeyed north — or as one Minnesota newspaper later put it, “drifted into the Yukon country along with other debris of humanity before the great strike.” He and four friends were prospecting on the Yukon River when the discovery happened. They rushed to Bonanza Creek but the entire waterway had already been locked up. Stander staked claims on nearby “Bonanza’s pup,” later renamed Eldorado Creek. It turned out to be the richest waterway in the Klondike!

And Stander lived the high life before leaving town in 1899. He became smitten with Dawson dancing girl Violet Raymond and moved her into his cabin on Eldorado Creek (the cabin’s chimney is still standing, on Klondike Gold’s ground). Stander bought Violet most of Dawson’s diamonds and lavished her with gold nuggets and jewelry. The power couple moved to Seattle and got married, visiting Paris, Japan and China on their honeymoon. They diversified into real estate, buying Seattle’s historic Holyoke building and building the 250-room Stander Hotel — one of America’s finest west of New York City.

But Stander liked his liquor; liquor fuelled his jealousy; the marriage went sideways. The couple divorced in 1906. Stander returned to the North and continued prospecting. However, he died penniless in 1952 in the Pioneers’ Home in Sitka, Alaska — a home built by one of Stander’s fellow Klondike tycoons for down-on-their-luck prospectors. Stay tuned for the next “Klondike King”!

Klondike Kings: Clarence (C.J.) Berry

C.J. Berry was a struggling fruit farmer in Selma, California who sold everything to seek his fortune in the North. Of a party of 40 that crossed the Chilkoot Pass in 1894, only Berry and two others made it to Forty Mile. It wasn’t the last time Berry beat the odds — he died wealthy and parlayed his gold rush fortune into a business empire that survives to this day.

Success did not come immediately, though. Berry struggled to survive the Northern winter of 1894-95, once going two months eating only beans while trapped in a remote area. From local First Nations, Berry picked up important tips on how to navigate the harsh climate. In 1895 he trekked back to California and married his childhood sweetheart, returning with her and his brother. Berry was tending bar in Forty Mile when George Carmack stopped by in late August 1896 and paid for his booze with impressive gold nuggets. Berry left for Rabbit (Bonanza) Creek immediately and managed to stake a claim there.

But Berry’s fortune was really born during a chance saloon encounter with Anton Stander a few weeks later in Forty Mile. Both men were restocking but Stander had no funds with him and was refused service at the general store. Berry grubstaked him, and a grateful Stander traded Berry half his Eldorado claim for half of Berry’s Bonanza claim. The Eldorado claim (Six Eldorado) turned out to be one of the richest pieces of land on Earth, a claim worked by Berry and two of his brothers. Berry and Stander later bought two adjoining claims and then split the entire land package between them. C.J. and Ethel Berry made their triumphant return to America on the Portland, the ship that docked in Seattle on July 17, 1897 as a feverish crowd waited.

Berry was sober, hard-working and ambitious in a camp where most successful prospectors squandered their fortunes on wine, women and song. Generous too: he left an oil can of gold nuggets and a bottle of whiskey at his Eldorado cabin door, inviting passersby to help themselves. Berry took out $1.5 million in 1897 dollars from his Eldorado claims; he and his brothers later struck it rich a second time in Alaska, before returning to California and buying oilfields. He pioneered the use of steam to melt the permafrost and his C.J. Dredging Co. mined gold using a dredge in Alaska. The fortune Berry built exists to this day — Berry Petroleum Corp. trades as BRY on the Nasdaq. And the C.J. Berry Foundation funds causes including arts and culture, health, education and conservation.

The Entrepreneur: Belinda Mulrooney

Women are largely a footnote in most Klondike accounts, reflecting a world where women could not yet vote. Even Klondike co-discoverer Kate Carmack gets only two brief references in Pierre Berton’s iconic history: Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899.

Yet one Klondike woman defied enormous odds to build a fortune in that man’s world. Belinda Mulrooney wielded her smarts and tenacity like some kind of late 20th century jujitsu master, becoming as rich and influential as any of the Klondike Kings — in her 20s! She did it without ever panning a creek or digging for a paystreak. Instead, the sharp-elbowed Irish immigrant “mined the miners,” becoming an expert on supply and demand, Klondike-style.

Bright, ambitious and tenacious, Mulrooney quickly tired of the conventional roles women were expected to play in America. In 1893, the 20-year-old ventured to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where a new invention called electricity was on display. Mulrooney built and operated a restaurant near the entrance and came away with $8,000. Working on a boat from San Francisco to Alaska, she took orders for women’s goods — and caught wind of the Bonanza strike. Mulrooney headed to Dawson in the spring of 1897. On the Chilkoot Pass, she bought the supplies of weary stampeders who gave up the quest.

Mulrooney brought several mysterious long tin cans on her long journey north. Inside were flimsy dresses, silk nightgowns and underwear, which were snapped up by the women of dusty, dirty Dawson. She also catered to men’s needs by opening restaurants offering more than the three Bs — bacon, beans and bread — and clean hotel rooms. Mulrooney made a fortune selling food, booze and rooms to hungry, thirsty, tired prospectors in hotels she built at Grand Forks (near the confluence of Bonanza and Eldorado) and in Dawson. The hotels also helped her gather invaluable intel from prospectors.

Mulrooney later fell in love with “Count Charles Eugene Carbonneau,” a French con man posing as an aristocrat, and the pair married in Dawson in 1901. They divorced in 1906 (after travelling around the world) and Mulrooney moved to Yakima, Washington in 1908, where she built a mansion known as the Carbonneau Castle. She died in 1967, aged 95, at a nursing home.

The Trump Family Fortune

Long before Donald J. Trump’s presidency … a century before The Art of the Deal and The Apprentice … a young German man named Freidrich Trump immigrated to America. The 16-year-old Freidrich — a barber’s apprentice — left in 1885, just before reaching conscription age. He took a steamship to New York and moved in with an older sister and her husband, working as a barber. He was too ambitious to cut hair for long.

In 1891 the young man went west to Seattle, where he bought and rebranded a restaurant. The eatery in the heart of Seattle’s red-light district also advertised “Rooms for Ladies,” a euphemism for prostitution. It was a business formula Trump returned to later when he decided to join the Klondike Gold Rush. Washington state was also where the young Trump made his first foray into real estate before leaving for Yukon. In an emerging mining town called Monte Cristo, Trump filed a mineral claim at a prime location and then built a hotel — on land he didn’t own.

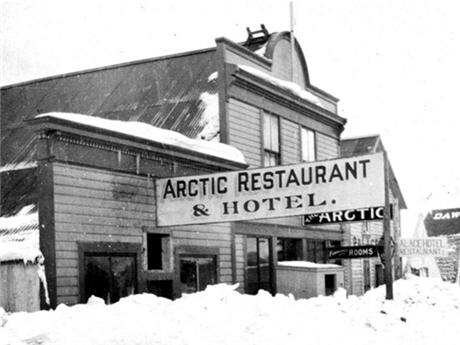

Monte Cristo went bust but Trump was already gone, having moved back to Seattle shortly after the Portland steamed in with its golden load. Trump headed north and in May 1898, opened the Arctic restaurant and hotel in Bennett, a raw frontier town on the route from Skagway to the Klondike goldfields. He made a small fortune providing stampeders with food (including fresh horse meat), drink and women. As a Yukon Sun writer put it, “For single men the Arctic has excellent accommodations as well as the best restaurant in Bennett, but I would not advise respectable women to go there to sleep as they are liable to hear that which would be repugnant to their feelings – and uttered, too, by the depraved of their own sex.”

The new Skagway to Whitehorse railroad bypassed Bennett, so Fred Trump took down his restaurant and shipped the wood to the railway terminus of Whitehorse, where he opened an even larger restaurant and inn. Trump stuck with his tried-and-true formula — food, wine and women — and added gambling. After a falling-out with his business partner, and ahead of a looming crackdown on prostitution, Trump took a fortune out of the Yukon and returned to his native Germany, before returning to America. Family ties to the Yukon endure to this day — the U.S. president’s son, Donald Trump Jr., has travelled to the Northern Territory several times on hunting trips.

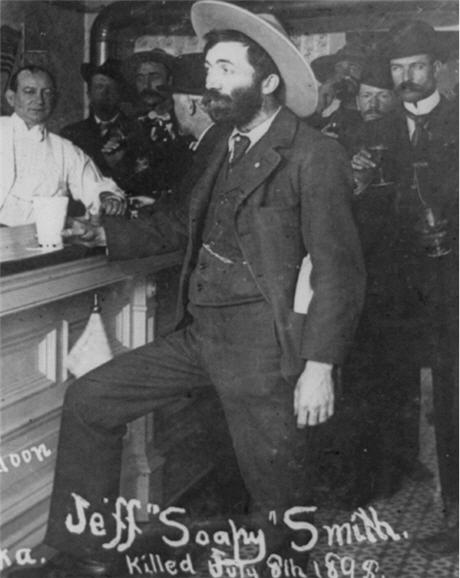

The Scoundrel: Soapy Smith

Jefferson Randolph (Soapy) Smith II was already an accomplished con man and crime boss before ever setting foot in the Klondike. He operated the “prize package soap racket” across the western U.S. for 20 years before branching out into saloons, gambling halls, auction houses — and election-fixing. The soap scam involved selling soap bars on a street corner, wrapping $1 to $100 in paper money into some, and then wrapping plain paper over all of them. The only “winners” would be Smith’s henchmen; he would declare that the $100 soap bar had yet to be won and auction off the remaining soap bars to the highest bidder — before getting out of town.

Soapy became Denver’s most powerful crime boss, protecting his empire by buying influence at city hall. As the Klondike hype built, Soapy spotted an opportunity. He moved to Seattle and casually announced to an acquaintance that he was going to run Skagway. He later moved to the Alaskan port city — a busy stop for stampeders — and went to work.

Soapy’s crews specialized in separating people from their money, and their gold. His men posed as clergymen and reporters, in Skagway and on the ships to and from Skagway, and befriended stampeders to determine who had money and how much. They used traditional methods, such as theft and rigged card and poker games, as well as more innovative scams. Soapy opened a fake telegraph office in 1898 but the wires only went as far as the wall (Skagway was not connected by telegraph until 1901). Soapy collected from families sending messages to loved ones, and getting “messages” back. Soapy opened a saloon that became known as “the real city hall” and had Skagway’s deputy U.S. marshal on the payroll, ensuring he wouldn’t be arrested. Soapy’s enemies formed a vigilante committee, but the con man had enough of a following to land a spot as grand marshal in Skagway’s 1898 Independence Day parade. Four days later, he was shot dead in a gunfight on Juneau wharf.

The Epicentre: Dawson City

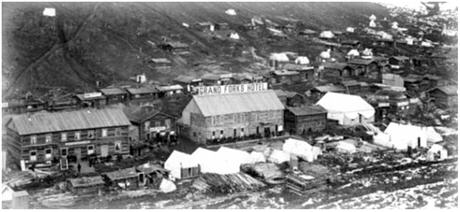

The story of how the swampland at the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike rivers became Dawson City begins with Joe Ladue, who staked a townsite instead of claims. A failed prospector, Ladue was running a trading post and sawmill on the Yukon River when news of the discovery hit. Ladue had a vision — he loaded his sawmill onto a raft and floated it to the new townsite. He named Dawson City after government geologist George M. Dawson. In September 1896, Ladue’s cabin (later a saloon) became the first building in the new mining camp.

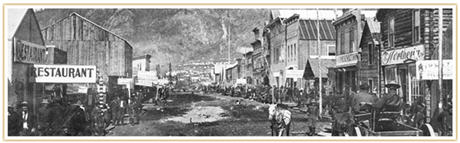

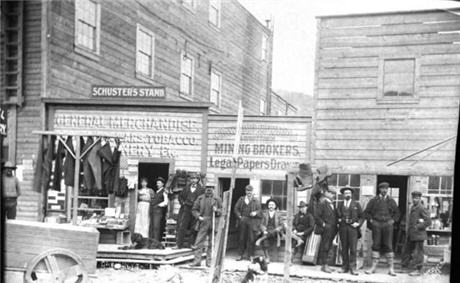

Stampeders flooded in, buying Ladue’s lumber and lots and turning Dawson into a sprawling town of tents and cabins. Very quickly, however, there were shortages of food and supplies, not to mention disease outbreaks due to unsanitary conditions. Sewage was dumped into the street, garbage into the river. The Yukon River flooded its banks in the spring of 1898, submerging much of the townsite. Fire was also a constant threat, and several blazes raced through the makeshift wood and canvas buildings. By summer, Dawson’s population closed in on 40,000 — the largest city west of Winnipeg and much larger than Vancouver or Victoria.

Dawson was a rambunctious, exciting and international town. Some of the new arrivals, however, promptly got back on boats out of town. Of those who stayed, many never ventured into the goldfields — but there were other things to do. Whiskey flowed freely in the saloons, fortunes (in gold and claims) changed hands in card games, and there was fierce competition among prospectors for the relatively few females there. Some Dawson residents drank champagne and ate caviar for breakfast; many subsisted on stale bread, beans and lard. A few of the latter became millionaires.

Ladue exited the Klondike with his fortune and sailed into San Francisco on board the Excelsior, the first gold ship. He was a multi-millionaire, with more than enough money to marry his childhood sweetheart back in New York. But enduring 13 hard winters had taken its toll on his body. Ladue died in 1900.

As for Dawson City, some things have changed: planes fly in and out on a recently paved runway. Some things haven’t: the dirt streets, raised wooden sidewalks and dancing girls. And if you stop by Diamond Tooth Gertie’s casino, you can see placer miners gambling with gold mining profits — or bet against them.

Dancing Hall Girls

Where there were miners, there were dance hall girls. And with a ratio of about 10 men for every one woman in Dawson City, the dancers were bound to be popular. For men accustomed to a monotonous, hardscrabble life, the dance hall girls were flashes of colour, softness and personality. And for the women, hooking up with the right (wealthy) prospector could mean a ticket out of the Klondike and back to civilization! Often, however, the alliances often didn’t work out.

The most famous dancing girl was probably Kathleen “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, a former New York City chorus girl. As talented at flirting as she was at dancing, Rockwell arrived in Dawson City as a teenager in 1898. According to legend, Klondike Kate made $30,000 in her first year in Dawson City. She fell in love with a Greek waiter with an interest in theatre named Alexander Pantages (he later became a U.S. movie mogul) and they started a stormy love affair that lasted for years before ending in a lawsuit. Klondike Kate capitalized on her dance-hall popularity on the “Outside” and died in 1957 in Oregon.

The most famous dancing girl was probably Kathleen “Klondike Kate” Rockwell, a former New York City chorus girl. As talented at flirting as she was at dancing, Rockwell arrived in Dawson City as a teenager in 1898. According to legend, Klondike Kate made $30,000 in her first year in Dawson City. She fell in love with a Greek waiter with an interest in theatre named Alexander Pantages (he later became a U.S. movie mogul) and they started a stormy love affair that lasted for years before ending in a lawsuit. Klondike Kate capitalized on her dance-hall popularity on the “Outside” and died in 1957 in Oregon.

Another whose legacy lives on is Mary (Gertie) Isobel Lovejoy, who inspired Diamond Tooth Gerties — Canada’s first legalized gambling hall. Lovejoy was known for the tiny diamond embedded between her front teeth as well as her alliances with influential Dawson City men, including U.S. Consul James McCook and Charles Tabor, Dawson City’s most prominent lawyer (whom she married). Diamond Tooth Gerties, run by the Klondike Visitors Association, features dancing girls several times a night during the summer, in homage to Dawson’s roots. The casino’s blackjack, roulette and card games are also a throwback to Dawson City’s heritage.

Dance hall girl and opera singer Violet Raymond caught the eye of Klondike King Anton Stander soon after arriving in Dawson City from Juneau. Stander fell hard for Raymond and lavished her with gold and diamonds. She moved into his cabin at Eldorado Creek and later married him in 1901, in San Francisco. They settled in Seattle after travelling around the world, with stops in Japan, China and Paris. The couple diversified into real estate and built the 250-room Stander Hotel in Seattle (it was demolished in 1930). But the marriage went sideways and their messy divorce — which included a literal division of the luxurious Stander hotel building — was front-page newspaper fodder in Seattle. One remnant of the relationship that still stands, surrounded by overgrowth, is part of Anton Stander’s chimney at his cabin site above Eldorado Creek, on Klondike Gold ground.

The Dredges

While the Klondike Gold Rush peaked between 1897 and 1899, gold has been mined continuously ever since. Starting in the early 1900s, though, shovels and sluice boxes gave way to mechanization in the form of dredges. As treasure seekers departed the Klondike for other finds, the business of digging up gold shifted from plucky prospectors to corporate conglomerates. Two of the main players were backed by the wealthy Rothschild and Guggenheim families.

Dredges are floating excavators that work on the same principle as older methods of placer gold mining, but on a much larger scale. Mechanized buckets on a bucketline scoop up sand, gravel and dirt, which is continuously fed into the dredge. Inside, it is washed and shaken; the heavier gold remains and the waste is spit out the back of the dredge on a conveyor belt. The modern-day visitor flying into the Dawson airport will see kilometres of these tailings snaking through the Klondike River valley.

As the most productive creeks were depleted, the dredge allowed higher volumes of material to be processed at much lower costs. The Klondike’s most well-preserved, and well-known, dredge is probably Dredge No. 4, which has been restored and is a National Historic site. It was built in 1912 for the Canadian Klondike Mining Company and operated on Bonanza Creek until 1959. It is an eight-storey monster that weighs 3,000 tonnes. Keeping the intake and waste conveyors clear of debris was a vital task — if the back end got clogged, the weight would sink the dredge in a matter of minutes.

Dredges are part of Klondike’s history and they relegated Grand Forks to history. The town where Belinda Mulrooney ran her legendary Grand Forks Hotel was situated between Discovery Claim on Bonanza and the mouth of Eldorado Creek. Its prime location meant that eventually the town was destined to be dredged, including the buildings, leaving few traces.

Modern-day gold miner and TV star Tony Beets (Gold Rush, Discovery Channel) brought dredge mining back to the Yukon. The former dairy farmer reconstructed a 70-year-old dredge and is mining gold in the Klondike, with plans to increase his dredging operations. And Yukon’s historic dredges, which are mostly in ruins, also live on through Iain Weatherston of Klondike Dredge Wood in Dawson City. Weatherston salvages the old-growth fir and metal and makes hand-crafted art, picture frames and furniture pieces from them.

The New Mine

Rich placer creeks ensured the term “Klondike” became synonymous with gold. Later, dredges and large-scale silver and base-metals mines established the Yukon as one of the world’s premier mining jurisdictions. But despite that rich history, the Canadian territory has not had an operating bedrock gold mine for almost two decades. In 2002, the Brewery Creek gold mine 55 kilometres east of Dawson City shut down after gold dropped below US$300 an ounce. And in 2018, Capstone’s Minto copper-gold mine shut down — leaving the Yukon without an operating mine.

Gold mining is back in a big way. John McConnell’s Victoria Gold (VIT-V) is in the final stages of building its Eagle gold mine east of Dawson City. Commercial production is pegged for September and Eagle will be the largest gold mine in Yukon’s history. The mine is projected to produce about 200,000 ounces of gold a year, life of mine, at operating costs of US$539 an ounce. It’s rare for a junior mining company to successfully take a mine into production but Victoria Gold is on the cusp of that achievement.

In addition to reviving Yukon’s golden legacy, Eagle will deliver much-needed revenues to the Yukon government. And it’s part of a rebirth of mining in the Yukon, which is once again buzzing with activity after a long bear market. Other mines that could re-open in coming years include:

• Brewery Creek, now owned by Golden Predator

• Alexco’s Keno Hill high-grade silver mine

• The Minto copper mine, recently purchased by U.K.-listed Pembridge Resources.

On the exploration front, the Klondike remains a beehive of activity, with Klondike Gold leading the way. Klondike Gold is currently drilling at the Lone Star Zone, part of a $2-million, 67-hole 2019 summer exploration program. Lone Star is directly above Eldorado Creek, the richest gold-producing waterway in the Klondike and the creek that made Klondike Kings Anton Stander and Clarence Berry fortunes.

About the author: James Kwantes is the editor and publisher of Resource Opportunities, a subscriber-supported investment newsletter focused on high-potential mining stocks. He is a longtime journalist who is the former mining writer at The Vancouver Sun newspaper. Use coupon code CEO at ResourceOpportunities.com to save $US100 off regular subscription prices of $US299 for 1 year or $449 for 2 years.