By Gwen Preston, Resource Maven

Licensed for reprint

It was less than three weeks ago that EMX Royalty announced its big deal to buy a portfolio of royalties from SSR Mining. When I talked with President Dave Cole about that deal, he made a comment that stuck with me: “Deals beget deals, you know. Watch out.”

I didn’t convey what he’d said at the time because it wasn’t enough on its own. But I’ve known Dave for 15 years and I know he holds his cards – EMX’s cards – close. That’s why the comment stuck: he wouldn’t have said anything unless something else was pretty close to the finish line.

Turns out something was. Last week EMX announced another large deal, this time to buy a 0.418% NSR royalty on the operating Caserones copper-molybdenum mine in Chile.

The price tag is US$34 million. So yes, it’s another large chunk of change. And no, EMX does not have that on hand. So to fund this acquisition EMX is taking out a short-term loan from Sprott Resource Lending.

More accurately: EMX had announced a small loan from Sprott related to the SSR deal, US$10 million to pad working capital and give capacity for small deals that might come around. To fund the Caserones royalty EMX is boosting that small loan to US$44 million.

It’s a big loan with a not-small interest rate of 7%. But it’s only a one-year facility. The short time frame is (1) a reminder that EMX took this cash because it was available quickly (Sprott is a friendly group that knows resources, so they could do the deal quickly), not because it’s some kind of long-term solution, and (2) a sign that EMX will deal with the debt differently within the next 12 months.

They will pay part of it down, for starters. I’ll describe EMX’s expected royalty cash flows later in the article but the bottom line is that the company will have US$30 million coming in the door in 2022. It’s safe to assume that this balance sheet-cautious group will put a good part of those funds towards reducing this outstanding debt. As for whatever is left, EMX has options: sell assets, refinance with a bank at a lower rate, or finance if time and price seem right.

So while the debt will have EMX paying Sprott between US$3 and US$6 million in debt over the next 12 months, the Sprott line is making the deal possible and is not going to weigh the company down for long, in my opinion.

That’s where the cash is coming from.

What is it buying? Caserones is an open pit mine tapping a significant copper-moly deposit in the Atacama region of Chile. The mine is owned by JX Nippon Mining & Metals, which consolidated ownership last fall by buying out its two Japanese partners.

The friendly partners did not disclose terms but before that news broke the market had speculated Nippon would sell its 52% stake for roughly $1 billion.

I mention that as one way to convey the scale at Caserones. This is a big operation. It produces copper and moly concentrates from a conventional crush-mill-float plant and produces copper cathodes from a dump leach and SXEW plant. In 2020 it produced 104,917 tonnes of copper in concentrates, 2,453 tonnes of moly in concentrates, and 22,056 tonnes of copper cathode.

It started producing in 2014 after a build that saw costs more than double (from $2 billion to $4.2 billion). And things didn’t get easier after that: the mine struggled to meet expectations because of ramp up problems and the parent company racked up over $50 million in infraction charges from Chile’s Superintendency of the Environment for breaching environmental rules.

But things are now improving. While it took years to get through start-up challenges, the mine has reliably produced at least 100,000 tonnes of copper in concentrate for the last few years and Nippon is working to reach nameplate (150,000 tonnes of copper in concentrate plus 30,000 tonnes in cathode) over the next few years.

I should note: EMX is not buying the royalty from Nippon. Instead, EMX and Altus Strategies are together buying a 0.836% NSR royalty on the mine that they will split 50-50. They are buying it from one of the two groups that own a 2.88% NSR royalty on the mine. Those groups are the teams that discovered the deposit and this deal provides the one group with US$68.2 million today for less than half of the royalty that it owns.

To be very clear: this is a cash-flowing royalty on a large mine with 17 years of mine life on the books, excellent exploration upside (the project saw no exploration during construction and ramp up challenges but Nippon is now keen to start exploring again), and an output profile that could grow as much as 30% in the next few years if it indeed reaches nameplate capacity.

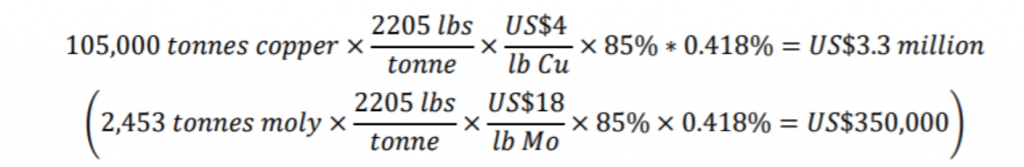

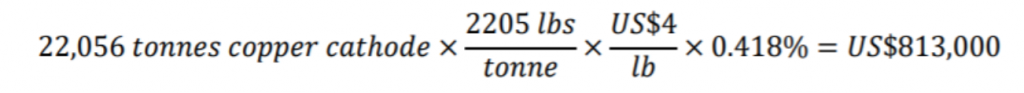

How much cash? Let’s do a little math.

Net Smelter Return royalties are percentages of the amount a smelter pays the miner for the metal it produces from a mine. Looked at from the other side, they are percentages of the value of the metals produced minus what the smelter charges for processing.

It makes for pretty easy math, on a rough level.

Here I’m assuming a copper price of US$4 per lb., a moly price of US$18 per lb, and that smelter and transport charges eat up 15% of the value.

The copper in cathode math is even easier, as there are essentially no smelting costs involved. That means a NSR royalty holder basically gets its percentage of the value of the copper produced.

So this royalty will pay EMX US$4.4 million annually, starting tomorrow. Payout will of course be more if copper stays above US$4 per lb.

And it could increase as much as 30% if the mine does reach its throughput potential. And it will pay for years. As I noted, it has a 17-year mine life based on delineated reserves but the team at EMX sees good reason to believe Nippon will find more. There has been no exploration since 2005. 3 Is US$34 million a good price for something that pays out US$4.4 million annually and should do so (assuming copper price and mine operation stability) for almost 20 years? That’s an almost 8-year payback!

Yes…but I’ve noted before that it’s very tough to value royalties. What matters here is that EMX is moving into the big leagues.

Investors have learned to love royalty companies because they provide exposure to metal prices (good when they’re rising!) without being miners themselves. Not being miners means royalty companies don’t have to find new deposits, plan and permit and build new operations, operate mines, and employ many thousands of people to accomplish all these tasks. Instead, royalty companies have small staff (some of the largest royalty companies out there, the Franco Nevadas and Wheaton Precious Metals of the world, employ just a few dozen people) and limited operational costs.

What royalty companies have to bear instead is the cost of capital to establish a good portfolio of assets. That costs comes in whatever form the company chooses (or can get): share dilution, loans, asset sales if possible. Investors hate dilution but loans require payments…and choosing the wrong cost of capital balance can sink a company.

The reason: royalty companies can either pay a lot for assets that cash flow now or pay a little for assets that will cash flow a long time from now, or anything in between. For years, royalty companies primarily did the former – paid smaller amounts now for cash flows down the road.

That’s now changed. Several of the royalty deals that debuted over the last few years went big off the line. They raised huge amounts of capital and immediately spent most of it buying cash 11 flowing royalties. To generalize, I would say EMX’s Caserones deal has a better rate of return than most of the deals that fall into that category.

But even though those companies spent huge amounts of money to establish immediate cash flows in deals with low rates of return, the market swooned.

The following is a very brief history of Maverix Metals. This royalty company debuted in mid2016. In the five years since, MMX has spent US$205 million and 166 million shares (at an average price well below its current share price, probably around $1.50) buying royalties. It has also closed on several credit facilities, though most are now repaid.

For that, the company recorded $33 million in royalty revenue in 2020.

It would take many days and pages to properly analyze those transactions and rates of return, but the very rough math is that Maverix has spent $455 million in cash and share capital to establish 30,000 gold equivalent ounces of annual income worth $33 million. On the surface, it’s not a great rate of return.

But they do it in the hunt for a higher multiple. This is another part of the royalty game that’s hard to assess: how valuation multiples increase with scale. We know that bigger royalty revenues beget bigger multiples (which means the market bestows greater valuation per royalty ounce or dollar).

This rough chart is a very imperfect representation of what I’m trying to say, but it’s the best I could find. The concept is that market valuations rise relative to gold equivalent ounces coming in the door – as the scale of royalty payments increases, the market gives a higher multiple.

That relationship means scale matters in creating a company with a high market valuation. And that is why so many of the royalty players that have debuted in the last five years have clearly chased scale.

EMX has never followed that path. Rather than a deal-aggressive new player, EMX has been growing an organic royalty portfolio for 17 years. For the first 10 of those years the company was focused on project generation; about five years ago it switched focus to royalties and strategic investments.

But that switch did not bring about a change in corporate culture. And the culture at EMX is

• Use technical and global operations strength to find and act on opportunities others will not see or understand

• Use partner payments to fund operations (raise capital only when necessary to preserve tight share structure)

• Demand good returns (don’t trade money now for money later just to be able to announce deals, as Dave Cole always says)

This approach is distinctly different, as it’s based in value rather than momentum. EMX never wanted to chase deals, never wanted to trade dollars in the hunt for a re-rating that may or may not stick.

So why the deals now? Two reasons, both important:

1. Their carefully built royalty portfolio is closing in on some big paydays. Within a few years, two royalties in their portfolio – a 0.5% NSR royalty on the Timok mine and a 4% NSR royalty on the Balya mine – will start churning out significant cash. Both mines are starting production now and just need to get through the bumps of ramp up. As such it’s safe to say EMX is close to a re-rating anyway.

2. EMX had cash in the bank and was able to find two good deals. The SSR deal provides a royalty that pays out huge amounts for a short time (US$15M+ a year for two years); the payout declines thereafter but those big years bridge the gap until Timok and Balya start generating big dollars. And the Caserones deal is a good return on a long-life copper asset where they see strong growth potential; it just makes financial sense.

Bridging the cash flow gap with the SSR deal should pull EMX’s valuation re-rating forward by a year or two. Adding the Caserones royalty underlines the justification for that re-rating by adding a stable and long-lived revenue line.

Following news of the SSR deal, I estimated that EMX is likely to pull in US$25 million in royalty income in 2022, versus just $1.2 million last year. Even if my math was optimistic, the Caserones deal now makes that certain, and likely lifts it closer to US$30 million.

That kind of cash should enable EMX to repay a fair chunk of the Sprott loan while still doing what it does, which is scour the world for royalties available for the right price and promising projects they can buy (and then sell, retaining a royalty) or invest in.

This is a transformational change for EMX. Let me reiterate: last year they brought in only US$1.2 million in royalty revenue. Next year they will, I think, rake in US$30 million. I discussed 13 how royalty companies get higher market multiples are their royalty incomes rise, but the biggest re-rating comes at the start, when a company moves from not really making money to banking free cash flow.

Usually that change happens over time. With these two deals piling on top of the royalties it already owns that are about to start paying, EMX is making this move in a very big and sudden way.

And I think that will lead to a big and fairly sudden re-rating for EMX. I think it’s very reasonable to expect a 50% share price gain over the next 16 months. And it could be more.

EDITORIAL POLICY AND COPYRIGHT: Companies are selected based solely on merit; fees are not paid. This document is protected by copyright laws and may not be reproduced in any form for other than personal use without prior written consent from the publisher.

DISCLAIMER: The information in this publication is not intended to be, nor shall constitute, an offer to sell or solicit any offer to buy any security. The information presented on this website is subject to change without notice, and neither Resource Maven (Maven) nor its affiliates assume any responsibility to update this information. Maven is not registered as a securities broker-dealer or an investment adviser in any jurisdiction. Additionally, it is not intended to be a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in the material. Maven cannot and does not assess, verify or guarantee the adequacy, accuracy or completeness of any information, the suitability or profitability of any particular investment, or the potential value of any investment or informational source. Additionally, Maven in no way warrants the solvency, financial condition, or investment advisability of any of the securities mentioned. Furthermore, Maven accepts no liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of our product, website, or other content. The reader bears responsibility for his/her own investment research and decisions and should seek the advice of a qualified investment advisor and investigate and fully understand any and all risks before investing. Information and statistical data contained in this website were obtained or derived from sources believed to be reliable. However, Maven does not represent that any such information, opinion or statistical data is accurate or complete and should not be relied upon as such. This publication may provide addresses of, or contain hyperlinks to, Internet websites. Maven has not reviewed the Internet website of any third party and takes no responsibility for the contents thereof. Each such address or hyperlink is provided solely for the convenience and information of this website’s users, and the content of linked third-party websites is not in any way incorporated into this website. Those who choose to access such thirdparty websites or follow such hyperlinks do so at their own risk. The publisher, owner, writer or their affiliates may own securities of or may have participated in the financings of some or all of the companies mentioned in this publication.